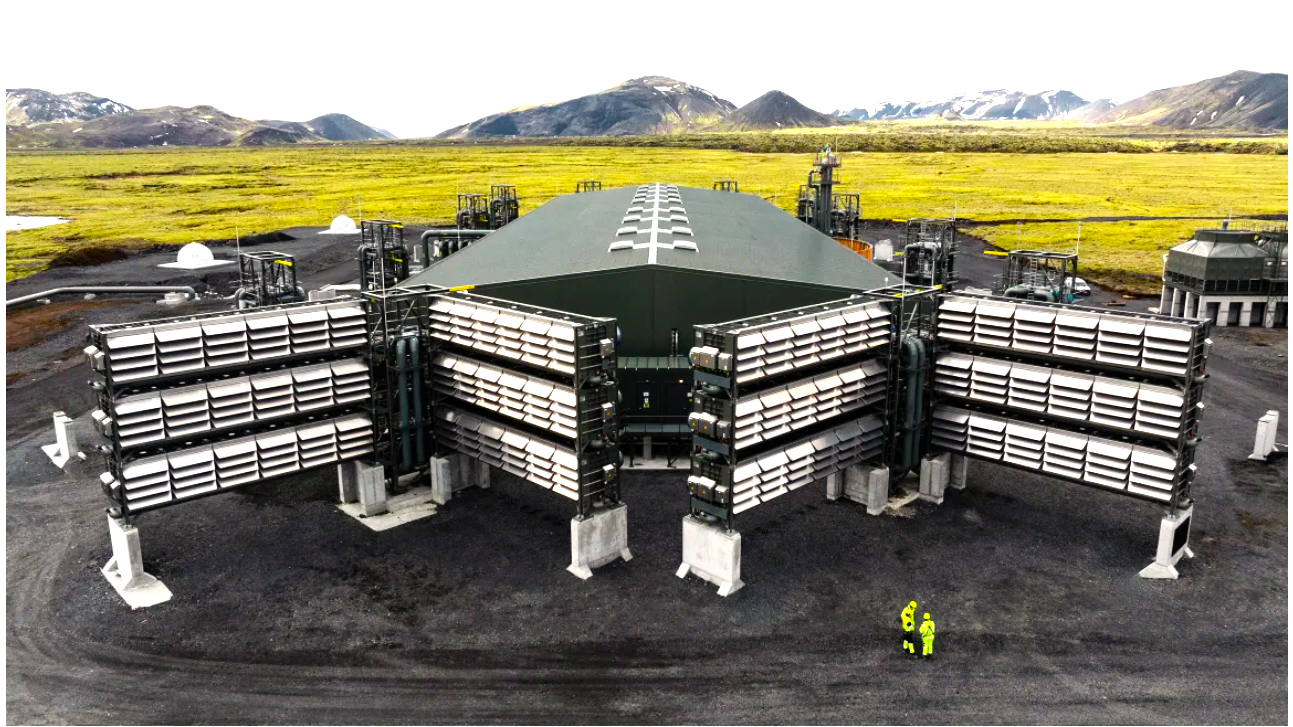

On May 8, 2024, the world witnessed the inauguration of a colossal initiative to combat climate change head-on: the largest-ever direct air capture plant. Developed by Swiss firm Climeworks, this mammoth facility in Iceland dwarfs its predecessor, Orca, by a factor of ten. Direct air capture (DAC) technology is the backbone of this endeavour, functioning like a massive vacuum to extract carbon from the atmosphere using specialised chemicals.

Once captured, this carbon can be stored underground, repurposed, or even converted into solid materials, offering a promising avenue in the fight against global warming.

Climeworks is set to utilise Iceland's plentiful, clean geothermal energy to power its ambitious carbon sequestration project in collaboration with Icelandic company Carbfix. This innovative endeavour aims to transport carbon underground, where it will transform into stone, effectively locking it away permanently.

As humanity grapples with soaring carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, a beacon of hope emerges in the form of next-generation climate solutions like Direct Air Capture (DAC). These technologies, with their potential to revolutionize our approach to climate change, are gaining traction among both governmental bodies and private enterprises amidst the relentless burning of fossil fuels. In 2023, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations hit an unprecedented high, underscoring the urgent need for innovative solutions.

As the Earth's temperature continues to rise, inflicting severe repercussions on both humanity and ecosystems, a consensus among many scientists is emerging. Alongside swift reductions in fossil fuel usage, we must explore avenues for actively extracting carbon from the atmosphere.

However, it's important to acknowledge that the viability of carbon removal technologies such as DAC remains a subject of controversy. Critics argue that they are prohibitively expensive, voracious in their energy demands, and lack proven scalability. These are valid concerns that need to be addressed. Moreover, some climate advocates fear that prioritising these technologies could divert attention and resources away from urgently needed policies aimed at curbing fossil fuel consumption. It's crucial to consider these perspectives in our discussions.

Lili Fuhr, director of the fossil economy program at the Centre for International Environmental Law, has expressed reservations regarding carbon capture technologies, citing their inherent uncertainties and potential ecological risks.

Construction of Mammoth began in June 2022 by Climeworks, heralded as the world's largest carbon capture plant. Its modular design accommodates 72 "collector containers" that capture carbon from the air. Currently, 12 containers are operational, with more slated for installation in the coming months.

At full capacity, Mammoth is projected to remove 36,000 tonnes of carbon annually, equivalent to removing about 7,800 gas-powered cars from the road for a year.

While Climeworks didn't disclose the precise cost per ton of carbon removed, they indicated it leans closer to $1,000 than $100 per ton—a significant factor for the technology's affordability and viability.

During a recent discussion with journalists, Jan Wurzbacher, co-founder and co-CEO of Climeworks, emphasised the company's cost reduction and scalability trajectory. By 2030, their goal is to achieve a cost range of $300 to $350 per tonne, aiming for $100 per ton by 2050 as they expand the size of their facilities.

Stuart Haszeldine, a professor of carbon capture and storage at the University of Edinburgh, hailed the inauguration of the new plant as a significant stride in combating climate change. This facility will feature larger equipment designed for capturing carbon emissions. However, Haszeldine cautioned that despite this progress, current efforts still need to be revised compared to the monumental challenge.

According to the International Energy Agency, all existing carbon removal infrastructure worldwide can only manage to remove approximately 0.01 million metric tons of carbon annually. This figure needs to catch up to the 70 million tonnes per year required by 2030 to align with global climate objectives.

While other companies are also developing larger Direct Air Capture (DAC) plants, like the Stratos plant under construction in Texas, which aims to remove 500,000 tonnes of carbon per year, concerns arise regarding the utilisation of captured carbon, Occidental, the oil company backing the Stratos project, plans to either store the captured carbon underground or employ it in enhanced oil recovery, a process criticised for potentially prolonging fossil fuel extraction.

Despite these challenges, Climeworks remains optimistic about the potential of its technology. Wurzbacher outlined ambitious plans for the company, including scaling up to remove 1 million tonnes of carbon annually by 2030 and an astounding 1 billion tonnes by 2050. Notably, Climeworks is distinct from fossil fuel companies, positioning their technology as a vital tool in the fight against climate change.

Iceland hosts three aluminum smelters with a combined annual production nearing to around 900,000 tonnes of primary aluminum. The nation's allure to smelting enterprises, including those from the United States and various other countries, stems from its cost-effective and environmentally sustainable electricity generation methods, predominantly derived from geothermal and hydroelectric sources. This advantage is facilitated by the utilization of dams that harness the potent energy of glacial meltwater. Furthermore, Iceland's strategic geographical positioning includes accessible ports, enabling international entities to efficiently export their aluminum worldwide.

Responses